We are thrilled to report the successful graduation of another class of Unite Scholars from higher secondary school in Tanzania — A Levels, Form 5 & Form 6 — or the rough equivalent of high school in the United States. These 29 talented and hard-working young men and women have now officially completed our 2.5-year Unite Scholar & Mentorship Program and achieved a level of education that can be claimed by just ~3% of all Tanzanians. Our team, along with more than 100 members from our extended Unite community, gathered together at Unite Food Program headquarters in Dar es Salaam earlier this summer for days of celebrations and trainings for our new graduates. These talented young men and women are — thanks to every generous donor and sponsor who has helped support them — well on their way towards achieving independence and fulfilling their dreams.

Reflections from a few of our 2022 Unite Scholars

CLICK HERE TO HEAR A FEW SCHOLARS DISCUSS THEIR EXPERIENCES WITH UNITE

David graduated from Tabora Boys Secondary School where he majored in Physics, Chemistry & Mathematics. David scored DIVISION 1 on his Form 6 National Leaving Exam and is currently interning/teaching at the Sakapala Community Center while applying to universities across Tanzania. David dreams of becoming an actuary. Click HERE to see David speaking about the Unite Club that he helped launch and lead at Tabora Boys School.

Maria John graduated from Mtwara Girls Secondary School where she majored in Economics, Geography & Mathematics. Maria scored DIVISION 1 on her Form 6 National Leaving Exam and is currently interning at the Marangu School of Tourism and Vocational Training while applying to universities across the continent. Unite funded the building of a new house for Maria John and her family after their homestead disintegrated during the rains. Click HERE to watch a short video of the construction of Maria John’s new house. Maria dreams of becoming a psychologist or therapist to help counsel, care for and inspire those in need.

THE TOTAL ALL-INCLUSIVE* COST OF SPONSORING THESE 29 SCHOLARS FOR the past 2.5 YEARS HAS BEEN ~$180,000 — OR ABOUT $3,000 PER SCHOLAR PER YEAR.

This spring we welcomed 13 new Unite Scholars and invite your continued support to continue to execute and grow this program. Checks can be sent to Unite the World with Africa Foundation, 74 Leighton Road, Wellesley, MA 02482 or donations can be made here or by scanning the QR code below.

Elina graduated from Masasi Girls Secondary School where she majored in Physics, Geography & Mathematics. Elina has participated in two Yale University programs for African Scholars as well as a STEM boot camp. Elina scored DIVISION 2 on her Form 6 National Leaving Exam and is currently interning with Projekt Inspire while applying to universities across the continent. Elina dreams of working in tech. Click HERE to see Elina presenting at the Masasi Girls Unite Club in 2020.

Enock graduated from Same Boys Secondary School where he majored in Physics, Chemistry & Mathematics. Enock scored DIVISION 2 on his Form 6 National Leaving Exam and is currently interning at the Future Stars Football (soccer) Academy for at-risk youth while applying to universities across Tanzania. Enock dreams of becoming an engineer. Click HERE to see Enock demonstrate his amazing “football” skills.

Khadija graduated from Mringa High School where she majored in Economics, Commerce & Accounting. Khadija scored DIVISION 1 on her Form 6 National Leaving Exam and is currently working full-time in the accounting department of a retail store while applying to universities across Tanzania. Khadija dreams of becoming a successful businesswoman. Click HERE to see Khadija showing us the space in which she lives with her mother and sister in 2020. Unite has since helped to significantly renovate and upgrade the home space for the family.

Where does the money go?

Elements of the 2.5-year sponsorship package for these 29 Unite Scholars has included:

School fees & all school-related expenses including tuition fees, books, tutoring support, transportation and personal items - soap, shampoo, sanitary items, etc., sheets, mattresses, mosquito netting, trunks and padlocks, buckets and cleaning tools, and more.

Medical care for all Unite Scholars and for family members, as needed and as possible.

Creation of Unite Clubs at the Scholars’ schools. The Unite Club program includes weekly lessons covering Unite’s "Soft Skills of Professionalism” curriculum, the Unite Passion Project video-career-discovery program, the building and maintenance of Unite-sponsored organic gardens, and extensive tree planting campaigns; volunteer opportunities, and more. Unite provides the clubs with computers, projectors, microphones, phones, flash drives, all educational materials and training content, and more.

Intensive trainings with Unite Mentors and international guest speakers over school holidays.

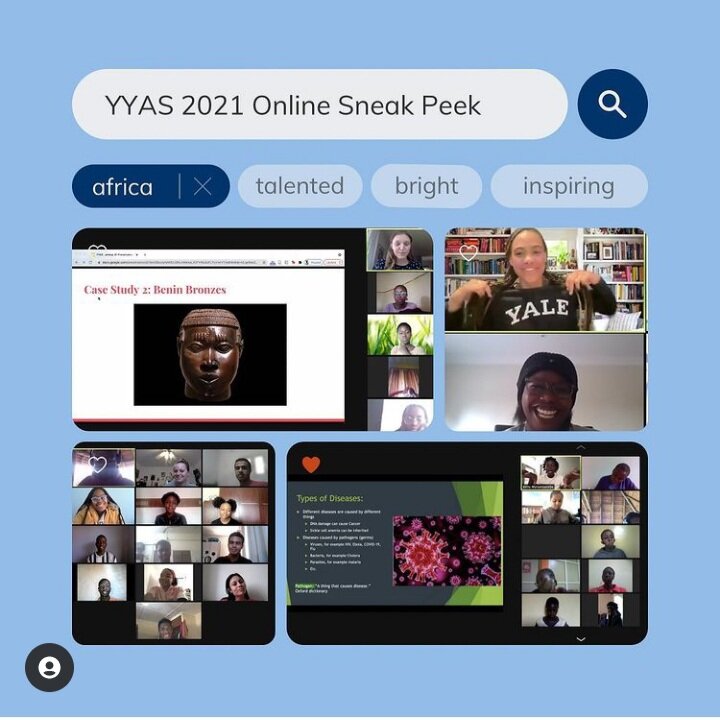

Application assistance, fees, and support for participation in international workshops including the Yale Young African Leaders Summit in 2021, the Yale Young African Scholars Online Training Program in 2022, and a STEM Bootcamp with PROJEKT INSPIRE.

Grants to launch small businesses. Each Unite Scholar received a grant during the time of COVID-19 to launch a small business. Businesses included small bakeries; sewing & tailoring services; small shops & restaurants; rabbit, chicken, and avocado farming; and others.

Unite Warrior For Change interest-free loans to further grow and develop their businesses.

Participation in the Unite Youth Ambassador Program. Click HERE to read the blog post introducing the program in 2020.

Participation in the Unite Blessing Campaign. Click HERE to read a blog post about the Blessing campaign.

A final Unite Scholar graduation ceremony and three-day training in July 2022. Click HERE to see the scholars dancing at the ceremony.

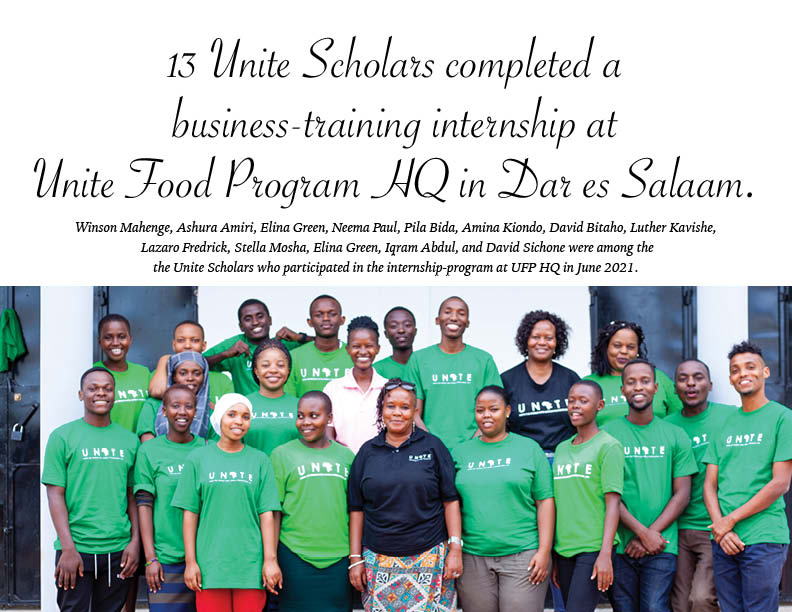

Paid internships at Unite Food Program Headquarters in Dar es Salaam and at Unite Food Program Outpost in Western Tanzania. Additionally, many of our graduates are now working in paid internships in the fields of accounting, teaching, sales and marketing, retail shop management, and farming.

University application support. Now is the time to apply for university loans and scholarships in Tanzania. Our Unite Mentors continue to work closely with our graduates assisting them with their applications (essay writing, CV creation, letters of recommendation, etc.).

Unite knows that our scholars’ success is directly linked to their family’s stability. To this end, Unite provides extensive support to their families. For these Kit Girl families, the support we have provided over the past two years includes:

Bicycles for safe and convenient transport

Home solar panels for power

COVID-19 relief items including sanitizers, masks, and food relief

Home renovations, beds, furniture, kitchen supplies, food, and school fees for all siblings for a scholar who lost her mother

Food gifts for Christmas, Ramadan, Mother’s Day, Easter, and birthdays.

Witness graduated from Tabora Girls Secondary School where she majored in Physics, Chemistry & Mathematics. Witness scored DIVISION 1 on her Form 6 National Leaving Exam and is currently interning at a library, tutoring students, and helping at her mother’s new restaurant (which was started with a Unite interest-free Warrior for Change loan) while also applying to universities across Tanzania. Witness dreams of working in medicine. Click HERE to see Witness introduce her family to Unite.

Amina graduated from Mringa High School where she majored in Economics, Commerce & Accounting. Amina scored DIVISION 1 on her Form 6 National Leaving Exam and is currently interning part-time as an accountant at a retail store while applying to universities across the country. Amina dreams of becoming a successful entrepreneur. Click HERE to see Amina speaking about her internship with Unite Food Program.

Zainabu — and her sister Zaituni — graduated from Masasi Girls Secondary School where they both majored in Chemistry, Biology & Geography. The girls both participated in the Yale Young African Scholars Online Training Program in 2021 and scored DIVISION 2 on their Form 6 National Leaving Exams. Zainabu and Zaituni are now interning at the Marangu School of Tourism and Vocational Training while applying to universities across the continent. Zainabu and Zaituni dream of working in the field of Environmental and/or Food Science. Click HERE to see Zainabu introducing her family and home to Unite in 2020. Click HERE to see Zaituni say Happy New Year in 2021.

Michael graduated from Same Boys Secondary School where he majored in Physics, Chemistry & Biology. Michael scored DIVISION 1 on his Form 6 National Leaving Exam and is currently serving in the Tanzanian National Service while also applying to universities across Tanzania. Michael dreams of working in medicine. Click HERE to see Michael’s first application video for Unite made in February 2020.